It was the author Joseph Conrad's ideas about "the main task" of art that inspired a significant change in how I thought about my goals as a creative musician. In his 1897 preface to a novel, he wrote, "A work that aspires, however humbly, to the status of art should carry its justification in every line." In other words, an artist's work is economical in expression so that every element contributes vitally to the whole. Conrad's idea of artistic justification in every line led me to fundamentally rethink my approach to jazz improvisation, shifting my aim from technical skill to structural unity and artistic intent.

Before I considered Conrad's observation, I thought the goal of jazz improvisation was simply to achieve an interesting extemporization based on a composition's melody, harmony, and rhythm. Perhaps what made it especially "interesting" was how it mystified the original composition’s basic materials of harmony. Much jazz pedagogy develops the tools to actualize that goal, focusing, for example, on the applications of scales, chord substitutions, complex rhythm and irregular meter. But does great skill in harmony and rhythm truly lead to more artful improvising?

Conrad's idea of artful "justification" requires not only skillfully executed ideas but also the presence of a larger structure or form that governs them. This inspired me to question the structural unity, or "justification in every line," of my improvisations on two levels: a macro-level, which considers what makes a solo feel complete; and a micro-level, which considers the usefulness of each musical element in relation to the larger form. I admire improvisers like Sonny Rollins and Keith Jarrett because their most inspired solos are organized like written compositions: each phrase logically progresses from one to the next, creating a structural form that builds toward a natural climax and conclusion.

To explore this, I sought a simple approach to make every element of the music (melody, rhythm, harmony) play a vital part in both the individual phrase and the larger form. A simple way to integrate phrase and form is to develop a single motif throughout the entire solo. In this approach, traditional vocabulary like chord substitutions, rhythms, and scales are not ends in themselves but tools to manipulate the motif and generate cohesive form. The application of this vocabulary at least justifies the presence of each musical phrase by its relatedness to the original idea.

To further explore this approach, two practical questions must be answered: what kind of motif one should use to build a clear form, and what are the means to become more comfortable spontaneously producing variations of the motif?

To answer the first question, the selection of a motif should be appropriate to the style of music. For instance, while improvising on jazz standards with a traditional bebop group, three appropriate motifs might be the song's original melody, a fragment of it, or a simple bebop rhythm. In a more progressive context, however, the soloist is free to choose any motif. Regardless of the context, selecting a simple motif is ideal because it is easier for both the improviser to manipulate and the listener to follow.

As for the second question—how to become more comfortable manipulating a motif in real time—the first step is to understand the character of the original idea, which allows you to practice inventing ways to modify it. You can write out variations on an easy composition and then adjust what is unsatisfactory. Ways to modify a motif include rhythmic displacement, modal transposition, decoration, inversion, rhythmic augmentation, and rhythmic diminution. Naturally, these can be combined.

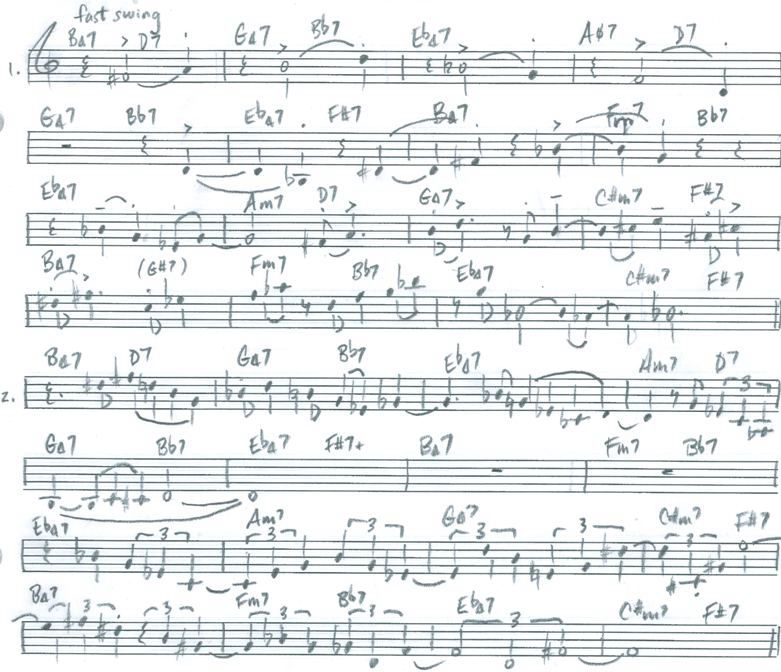

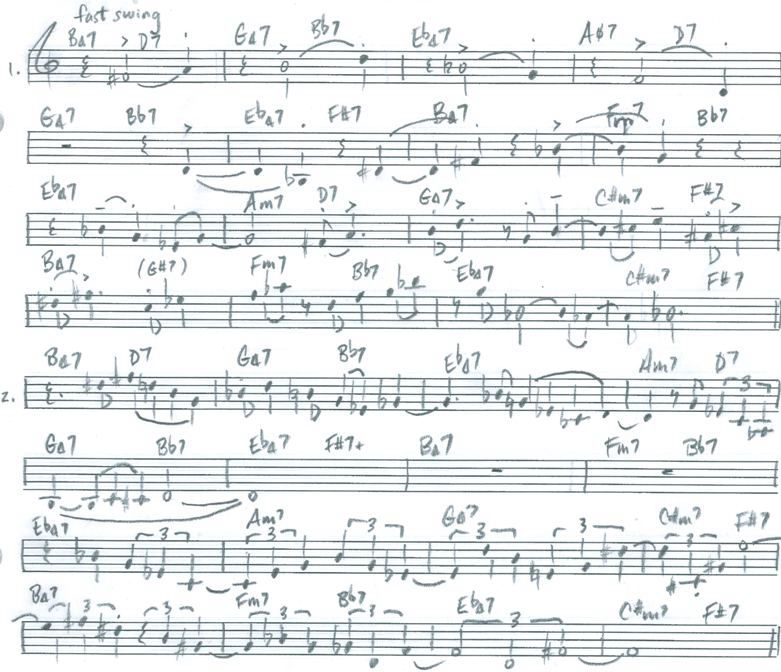

For a broader perspective, consider the above, an improvisation over John Coltrane's composition "Giant Steps." Since much of Coltrane's original melody and harmony moves in thirds, a natural choice for a motif is a third. The manipulation of that interval throughout my improvisation validates each phrase by its relatedness to the original motif. This creates a logical flow of ideas, forming a narrative that the listener can follow.

In conclusion, Joseph Conrad may seem an unlikely source of inspiration for a 21st-century improvisors, however, it was his conviction that music is "the art of arts." In his preface, Conrad strives for "... complete, unswerving devotion to the perfect blending of form and substance" in art. In this context, form is the structural unity of the composition, and substance refers to the musical elements economically expressed to justify the form in every line. This is a marked contrast to discussions limited to new, exotic scales, polyrhythms, or other innovations pursued as ends in themselves. Applying his wisdom, I believe, is a sure step toward producing more artistically mature improvisation, since clarity of form replaces the potentially directionless application of vocabulary.

David Braid